Lost in the history of man’s greatest global competition is the tragic fight and destruction of the Russian Wolves in the winter of 1916 and 1917. The only mention of their fate was a small article in the New York Times, published July 29, 1917, describing, in no vague terms, what was then considered to be the barbaric guerrilla warfare waged by the Wolves in defense of their homeland, and how the war between the Central Powers and the Allies was halted in order to end the nativist threat to their competitive jaunt through Europe.

The First World War, affectionately called “The Great War” by its inheritors, was by the fall of 1916 nearing the end of its first half. It was during this period that the Allied Powers, captained by the Russian Empire, had finally managed to wrest the critically strategic yet amorphous region around Minsk, Belarus, from the Central Powers, then being led by the German Empire. Following the Russian Empires acquisition of this region, both they and the Germans fell into a stupor.

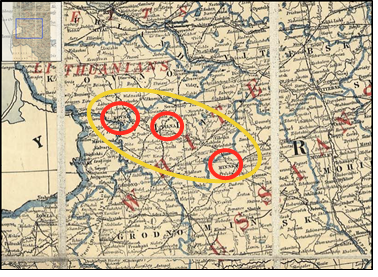

While the war itself was fought along a vast European front, its outcome was ultimately determined by the localized battles fought by individual groupings of troops. Such was the case in what was to become known as the Kovno-Wilna-Minsk front, where the Germans and Russians vied for greater strategic footing in the landmasses of Eastern Europe. Today, the city of Kovno is called Kaunas and the city of Wilna/Wilno is called Vilnius, both in Lithuania. Minsk is still Minsk, Belarus.

As “The Great War” raged across the Kovno-Wilna-Minsk front in the winter of 1916 and 1917, an unsuspecting local community found their homes being ransacked by the bored troops. These unwitting casualties were the Russian Wolf families who for centuries had called this ancient land their home.

Presumed range of Russian Wolf resistance during the Winter War of 1916–17

Key cities in the campaign for Eastern European domination, 1914–18

Presumed range of Russian Wolf resistance during the Winter War of 1916–17

Key cities in the campaign for Eastern European domination, 1914–18

Most of what historians have been able to unearth about the Russian Wolves during this period has been drawn from verbally communicated stories from their remaining descendants. Because of the relative recency of the conflict—just under a century ago from the date of this writing—it is deemed that the verbal histories are accurate. It is also unlikely that there is any revisionist history involved as it is evident, based on extensive anthropological work done in the past few decades, that honesty was a central tenet of Russian Wolf culture.

Russian Wolf life was rooted heavily in the gastronomy of the land, and over the centuries they had developed highly efficient tools and strategies to effectively take advantage of their local resources. By the time of “The Great War,” however, their lack of industrial infrastructure and their reliance on older technologies put them at a disadvantage when competing against the roving Huns and Ruskis. They were also entirely outnumbered; their culture revolved around nuclear families, each helmed by a paired patriarch and matriarch and supported by immediate family that generally numbered around 10–20 members. These families, colloquially called “packs,” were largely territorial, with each one staking claim to different areas of the region. To enforce these territorial claims, they developed complex methods of marking borders. The most common method was the use of scent markers, distilled or processed from the very same resources they used as foodstuffs. Verbal and visual signaling was also employed, but to a lesser extent.

While verbal histories have proven adequate in expanding our knowledge of Russian Wolf culture, the same has not been true about what we know of their collective fight against man. To this end, historians have had to study German and Russian war maps of “The Great War’s” Kovno-Wilna-Minsk front. However, since hardly any mention is made of the Russian Wolves within those maps, historians have had to make unbiased suppositions from deductive research and analysis of the extant materials, looking for any unexplainable troop movements or seemingly arbitrary plays.

It is known that during the summer and fall of 1916 the patriarchs and matriarchs of the various packs began organizing meetings in which resistance campaigns were discussed. The Russian and German combatants had reached a stalemate by that point, embracing a style of trench warfare that reflected their cultural life. It is unclear who, if anyone, took the lead in organizing the Wolf meetings, but by the winter of 1916 they began full-scale operations throughout their combined territory.

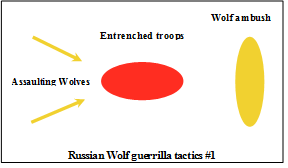

Based on anecdotal evidence and salvaged correspondence from soldiers on the front, we now know that the first Wolf actions began in late October and early November. The Wolves had two key advantages in those early months of combat: first, the Russian and German troops were immobile and easily ambushed and flanked; second, said troops were unprepared for the cold winter. The Russian Wolves recognized these two distinct tactical advantages and, using the already established familial ties, sent a steady stream of small units into the trenches. While the overall campaign involved a mobile, almost roving strategy of constant pressure, the individual unit tactics embraced what would later be championed by Adolf Hitler in the Second World War as “Blitzkrieg”: fast, furious, and uncompromising.

It is admittedly difficult to understand the rationale behind the overarching campaign movements as, at first glance, it looks haphazard. But as one begins to study the localized guerrilla tactics used—this is to say micro as opposed to macro—one can fully grasp the genius of the Russian Wolves’ campaign. Using their natural speed, stamina, and furor, they engaged in ingenious hit-and-run tactics all along the Kovno-Wilna-Minsk front, tangling with the entrenched Russian and German troops, tooth and nail.

Kovno-Wilno-Minsk front during the winter of 1916–17

Russian Empire lines German Empire lines Russian Wolf campaign strategy

These continued small-scale attacks, aided by their familiarity with the geography of the front, led to early successes that left hundreds of Germans and Russians in bloody bits and pieces. As morale along the front plummeted at seeing the Wolves’ furious attacks and the consequent mangled bodies, troops began to debate whether it truly was undesirable to die by the bullet or the shell. One unidentified German officer captured the desperation in a communique sent to his superiors in December of 1916, simply writing: “There are fucking wolves eating us!”

So effective was the Wolves’ guerrilla tactics, and so low was troop morale, that the German and Russian Empires finally called for a cease to their wrangling, uniting to plan a joint counterinsurgency effort. Their ultimate strategy was to unify their fronts into one long reinforced line supplemented with prototype German tanks, hindered only temporarily when traumatized troops from both Empires attempted to force their way into the safety of the few tanks available.

But the unified German and Russian counteroffensive proved to be highly effective. Russian Wolves began falling in droves to the newly concentrated fire from machine guns and rifles, with tanks launching forward attacks which the Wolves were unable to counter. In a last ditch effort, the Wolves began sending their cubs to combat the tanks by attacking the wheels of the treads, apparently in attempts to disable the vehicles and force their occupants out. This generally proved futile, however, with most of the cubs being crushed, then shot.

By February, with its warmer weather, the Russian Wolf offensive finally began to show signs of weakening. It was apparent that their numbers had been reduced greatly and their morale was almost non-existent, their attacks only occurring in the form of ravenous rages with little foresight put into them. Finally, the Russian Wolves dispersed in the face of overwhelming technological might, carried along with the retreating winter and never to regain their homeland.

Kovno-Wilno-Minsk front in the spring of 1917

Russian Empire lines German Empire lines Russian Wolf retreat strategy

Still, the Russian Wolf winter resistance was not without long-lasting impact. It is now accepted that the Kovno-Wilna-Minsk front’s no-mans-land, originally thought to be a product of incessant bombing and shelling from both Empires, was in fact a product of Russian Wolf resistance. This is hotly disputed by the current governments in both Germany and Russia who seem remiss in admitting they were held back by what is still considered to be a primitive culture. German Chancellor Angela Merkel herself has contested the current understanding of the Russian Wolves’ campaign strategy.

“Look at their movements. No one can say with any level of certitude that there was any method to it. It doesn’t even appear [the Russian Wolves] knew what the supposed ‘campaign strategy’ was,” she said in a press interview on August 9, 2013, bracketing “campaign strategy” in air quotes.

One wonders if the great Russian Wolves would still be prevalent today if they had simply let the Germans and Russians complete their jaunt. You will notice that the historical maps in no way show the boundaries of their territory, such is the degree of indifference to their rightful claim to what is Lithuania and Belarus. Even today, these young nations refuse to acknowledge and respect the Russian Wolves’ long ancestry rooted to the lands of that Baltic region. The descendants of the Russian Wolves are now a marginalized minority, relegated to ever shrinking rural areas with few resources and even fewer prospects for work, unable to compete against cheap labor provided by more domesticated brethren.

Fearing that to allow the Empires time would run the risk of there being one, clear winner, stronger than before and more difficult to defeat, the Russian Wolves waged a war to undermine both powers in their state of preoccupation and protect their homeland, a decision that ultimately proved to be fatally fateful.

Sources:

– http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?res=9E0DE3DD103BE03ABC4151DFB166838C609EDE (thank you /r/todayilearned)

– http://maps4u.lt/en/maps.php?img=Rusija_europoje_1918_&w=600&h=400&zoom=&cat=19

– http://www.westpoint.edu/history/SitePages/WWI.aspx

– Google image search

– A shit ton of Wikipedia